What Is Ovarian Cancer?

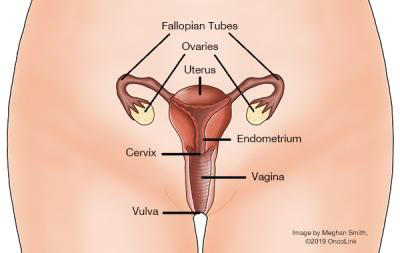

Ovarian cancer develops when cells in the ovaries begin to grow in an uncontrolled fashion. These cells also have the potential to invade nearby tissues or spread throughout the body. There can be benign or malignant ovarian tumors. Benign tumors or masses are not really cancer because they cannot spread or threaten someone’s life. The tumors that can spread throughout the body or invade nearby tissues represent true invasive cancer, and are called malignant tumors.

The distinction between benign and malignant tumors is very important in ovarian cancer because many ovarian tumors are benign. Also, sometimes persons (especially of younger age) can get ovarian cysts, which are collections of fluid in the ovaries that can occasionally grow large or become painful. However, ovarian cysts are not cancerous and should not be confused with ovarian cancer.

Cancers are characterized by the cells from which they originally form. The most common type of ovarian cancer is called epithelial ovarian cancer; it comes from cells that lie on the surface of the ovary known as epithelial cells. Epithelial ovarian cancer comprises about 90% of all ovarian cancers and usually occurs in older persons. About 5% of ovarian cancers are called germ cell ovarian cancers and arise from the ovarian cells that produce eggs. Germ cell ovarian cancers are more likely to affect younger persons. Another 5% of ovarian cancers are known as stromal ovarian cancers and develop from the cells in the ovary that hold the ovary together and produce hormones. These tumors can create symptoms by producing a large excess of female hormones. Each of these three types of ovarian cancer (epithelial, germ cell, stromal) contains many different subtypes of cancer that are distinguished based on how the cells look under a microscope. Discuss the exact category of ovarian cancer that you have with your provider so that you can get a sense of the particulars of your case.

Another type of cancer, called primary peritoneal cancer, is a malignant tumor arising from the peritoneum, the lining of the abdominal cavity. It tends to behave similarly to ovarian cancer, and they can look identical under the microscope. The treatments used are often the same as those used for ovarian cancer. This type of cancer can develop in persons with intact ovaries or in those who have had their ovaries removed.

What causes ovarian cancer and am I at risk?

In the U.S., it is estimated that 22,530 persons with ovaries will be diagnosed with ovarian cancer each year. Compared to other cancers, the incidence of ovarian cancer is quite rare.

Although there are several known risk factors for getting ovarian cancer, no one knows exactly why one woman gets it and another does not. The most significant risk factor for developing ovarian cancer is age. The median age at diagnosis is 63, although persons with genetic or family risk factors tend to be diagnosed with ovarian cancer at a younger age.

Other than age, the next most important risk factor for ovarian cancer is a family history of ovarian cancer. This is particularly important if your family members are affected at an early age. If your mother, sister, or daughters have had ovarian cancer, you have an increased risk for development of the disease. It is estimated that 7% to 10% of all ovarian cancers are the result of hereditary genetic syndromes. Genetic mutations that increase ovarian cancer risk include:

–Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome (HNPCC) or Lynch Syndrome.

–Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN 1).

–Breast and ovarian cancer syndrome (associated with mutations in either the gene BRCA1 or BRCA2).

–Peutz-Jeghers syndrome.

Other risk factors include being overweight, never having children or having them later in life, using fertility treatments, taking hormone therapy after menopause, smoking, and alcohol use. Remember that all risk factors are based on probabilities, and even someone without any risk factors can still get ovarian cancer.

How can I prevent ovarian cancer?

If you are a woman without a family history/genetic syndrome, the best way to prevent ovarian cancer is to alter whatever risk factors you have control over. For example, having children by age 30 and breastfeeding both reduce risk. Additionally, the use of oral contraceptives for 4 or more years is associated with a reduction in ovarian cancer risk in the general population. Bilateral tubal ligation and hysterectomy also decrease ovarian cancer risk. Keep in mind that any medication or surgical procedure has its own risks and should not be taken lightly.

Those who are carriers of one of the previously mentioned genetic syndromes face different decisions. They generally need to have more rigorous screening done for ovarian cancer. Some may elect to have their ovaries removed when they are still healthy (called a prophylactic oophorectomy). This should only be done when a woman is finished having children, and it can drastically reduce a woman’s chances for developing ovarian cancer (but not reduce the risk to zero). Before a woman decides to do this, she should have genetic testing and a significant amount of counseling from a healthcare provider who has experience with genetic diseases.

While a diet high in animal fats has been implicated in ovarian cancer, a diet rich in fruits and vegetables may have a small preventive effect. It has been suggested that supplementation with vitamins A, C, and E may decrease your risk. However, there are no official nutritional recommendations that can be made to prevent ovarian cancer.

What screening tests are used for ovarian cancer?

If you are at average risk for ovarian cancer there are no recommended screening tests. However, you should have a gynecological exam as often as your provider suggests. Your provider may be able to feel your ovaries during the bi-manual portion of the exam, and if any abnormalities are felt, you can be referred for further tests. The major limitation to this method is that early ovarian cancers aren’t usually felt on examination, and thus, are often missed.

What are the signs of ovarian cancer?

Ovarian cancer has been called a “silent killer” because it was thought that symptoms did not develop until the disease was advanced. More recently, ovarian cancer experts found that this was not true, and most had symptoms early on that were dismissed by themselves or their healthcare providers. The symptoms that are more likely seen in persons with ovarian cancer compared with healthy individuals include:

–Bloating.

–Pelvic or abdominal pain.

–Difficulty eating or feeling full quickly.

–Urinary symptoms (urgency or frequency).

–Unexpected weight loss

While these symptoms are more often due to other medical problems, persons with ovarian cancer report that the symptoms persist and represent a change from their normal. The frequency and number of these symptoms are also key factors in the diagnosis.

Other possible symptoms include fatigue, indigestion, back pain, painful intercourse, constipation and menstrual irregularities. Those who experience these symptoms almost daily for more than a few weeks should see a healthcare provider for evaluation.

How is ovarian cancer diagnosed?

The only way to determine for certain if a growth is cancer is to remove a piece of it and examine it in the lab. This procedure is called a biopsy. For ovarian cancer, the biopsy is most commonly done by removing the tumor during surgery.

In rare cases, a suspected ovarian cancer may be biopsied during a laparoscopy procedure or with a needle placed directly into the tumor through the skin of the abdomen. Usually the needle will be guided by either ultrasound or CT scan. This is only done if you cannot have surgery because of advanced cancer or some other serious medical condition, because there is concern that a biopsy could spread the cancer.

If you have ascites (fluid buildup inside the abdomen), samples of the fluid can also be used to diagnose the cancer. In this procedure, called paracentesis, the skin of the abdomen is numbed and a needle attached to a syringe is passed through the abdominal wall into the fluid in the abdominal cavity. Ultrasound may be used to guide the needle. The fluid is taken up into the syringe and then sent for analysis to see if it contains cancer cells.

In all these procedures, the tissue or fluid obtained is sent to the lab. There it is examined by a pathologist, a doctor who specializes in diagnosing and classifying diseases by examining cells under a microscope and using other lab tests. Your provider may also order other blood tests such as a CA-125 which is a tumor marker for ovarian cancer.

Although surgery is required for accurate staging, your providers may want to order some other tests to better characterize the mass/masses and look for distant spread. Tests like CT scans or MRIs can examine the pelvis and localized lymph nodes. Each patient is unique, so the specific tests people get will vary; but overall, your providers want to know as much about your particular tumor as possible so that they can plan the best available treatments.

How is ovarian cancer staged?

FIGO Staging System for Ovarian, Fallopian Tube, and Primary Peritoneal Cancer (8th ed., 2017)

|

FIGO Stage |

Description |

|---|---|

|

I |

Tumor limited to the ovaries (one or both) or fallopian tubes |

|

IA |

Tumor limited to one ovary or tube, no tumor on surface; no malignant cells in peritoneal washings or ascites |

|

IB |

Tumor limited to both ovaries or tubes, no tumor on surface; no malignant cells in peritoneal washings or ascites |

|

IC |

Tumor limited to one or both tubes with any of the following: |

|

IC1 |

Surgical spill |

|

IC2 |

Capsule ruptured before surgery or tumor on ovary or tube surface |

|

IC3 |

Malignant cells in ascites or peritoneal washings |

|

II |

Tumor involves one or both Fallopian tubes with pelvic extension |

|

IIA |

Extension and/or implants on the uterus and/or fallopian tube(s) and/or ovaries |

|

IIB |

Extension to and/or implants on other pelvic structures |

|

III |

Tumor involves one or both fallopian tubes, or primary peritoneal cancer with peritoneal metastasis outside the pelvis and/or metastasis to retroperitoneal lymph nodes |

|

IIIA2 |

Microscopic peritoneal metastasis outside the pelvis with or without positive retroperitoneal lymph nodes |

|

IIIA1 |

Positive retroperitoneal lymph nodes only |

|

IIIA1i |

Metastasis < 10mm in greatest diameter |

|

IIIA1ii |

Metastasis > 10mm in greatest diameter |

|

IIIB |

Macroscopic peritoneal metastasis outside the pelvis 2cm or less in greatest dimension with or without positive retroperitoneal lymph nodes |

|

IIIC |

Peritoneal metastasis outside the pelvis and more than 2cm in diameter with or without positive retroperitoneal lymph nodes |

|

IV |

Distant metastasis |

|

IVA |

Pleural effusion with positive cytology |

|

IVB |

Liver or splenic metastases, metastases to organs or lymph nodes outside the abdomen, involvement of the intestine |

|

IV |

Distant metastasis |

|

IVA |

Pleural effusion with positive cytology |

|

IVB |

Liver or splenic parenchymal metastases, metastases to extra-abdominal organs, transmural involvement of intestine |

FIGO Surgical Staging of Cervical Cancer (2018)

In addition to stage, the tumor grade will also be evaluated. This refers to how abnormal cells appear under a microscope. Low grade (or grade I) tumors appear the most like normal cells, whereas higher grade tumors (grade 3) appear very abnormal under the microscope. Higher-grade tumors may behave more aggressively than low-grade tumors. The staging system for ovarian and primary peritoneal cancer is also applied to malignant germ cell tumors, malignant sex cord-stromal tumors, and carcinosarcoma (malignant mixed Müllerian tumors).

How is ovarian cancer treated?

Surgery

Almost all persons with ovarian cancer will have some type of surgery in the course of their treatment. The purpose of surgery is first to diagnose and stage the cancer, as well as to remove as much of the cancer as possible. In early stage cancers (stage I and II), surgeons can often remove all of the visible cancer. Generally, those with ovarian cancer will have a hysterectomy (removal of the uterus) and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (removal of both ovaries and fallopian tubes) as part of their operation. There are some circumstances in which a woman may not have this entire operation, for example, if she has a very early stage cancer (IA) that looks favorable under the microscope (grade 1). This is often the case with germ cell ovarian tumors. If a woman’s tumor has these characteristics and she wishes to maintain the ability to have children, then the surgeon may remove only her diseased ovary and tube. Based on your stage and grade, your surgeon will discuss all the potential treatment options.

Persons who have more advanced disease (stage III or IV) will often have debulking surgeries. This means that the surgeon will attempt to remove as much disease as possible. Data collected in many studies has demonstrated that the more cancer that is removed, the better the long-term outcome for the patient. If the surgeon does not think they can successfully remove all of the cancer during the surgery, chemotherapy may be offered before the operation to help reduce the volume of disease.

Chemotherapy

Despite the fact that the tumors are removed during surgery, there is always a risk of recurrence because there may be microscopic cancer cells left that the surgeon cannot see or remove. In order to decrease a patient’s risk of recurrence, a patient may receive chemotherapy.

Chemotherapy is the use of anti-cancer medications that work systemically (throughout the entire body) and are administered either intravenously (directly into a vein), directly into the abdomen (intraperitoneal, “IP”) or orally (by mouth). The vast majority of patients with ovarian cancer should be offered chemotherapy as well as surgery (adjuvant chemotherapy). The higher the stage of cancer, the more important it is that you receive chemotherapy. Generally, only very early stage cancers (early stage I) that look favorable under the microscope (grade 1 or 2) can be treated with surgery alone. Any woman with a more advanced stage or grade ovarian cancer should be offered chemotherapy.

For the treatment of ovarian cancers, chemotherapy is typically given intravenously. Some of the chemotherapy medications used in ovarian cancer treatment include: cisplatin, carboplatin, doxorubicin, topotecan, ifosfamide, doxorubicin liposomal, docetaxel, paclitaxel, altretamine, capecitabine, cyclophosphamide, etoposide, gemcitabine, pemetrexed, and vinorelbine. Most initial regimens contain a platinum compound chemotherapy, such as carboplatin, and a taxane, such as paclitaxel or docetaxel.

Hormonal therapies including aromatase inhibitors (example: letrozole), tamoxifen, and luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) agonists (example: leuprolide acetate), are used more commonly in ovarian stromal type tumors, but not typically in epithelial ovarian cancer.

There are also some targeted agents used in the treatment of ovarian cancer including bevacizumab, rucaparib, niraparib and olaparib. Bevacizumab is used to stop blood flow to the tumor and works best when given with chemotherapy. Olaparib (Lynparza), rucaparib (Rubraca), and niraparib (Zejula) are drugs known as a PARP (poly(ADP)-ribose polymerase) inhibitors, and are all taken daily by mouth as pills or capsules. PARP enzymes are normally involved in one pathway to help repair damaged DNA inside cells. The BRCA genes (BRCA1 and BRCA2) are also normally involved in a different pathway of DNA repair, and mutations in those genes can block that pathway. By blocking the PARP pathway, these drugs make it very hard for tumor cells with an abnormal BRCA gene to repair damaged DNA, which often leads to the death of these cells.If you are not known to have a BRCA mutation, your doctor might test your blood or saliva and your tumor to be before starting treatment with one of these drugs. Some of these drugs can be used in patients with or without a BRCA mutation.

There are advantages and disadvantages to each of the different regimens that your providers will discuss with you. Based on your health, your personal values and wishes, and potential impact of side effects, you can work with your healthcare providers to come up with the best regimen for your cancer and your lifestyle.

Follow-up Care and Survivorship

Once a patient has been treated for ovarian cancer, they need to be closely followed for a recurrence. At first, you will have follow-up visits fairly often, usually every few months. The longer you are free of disease, the less often you will have to go for checkups. Your healthcare provider will tell you when they want follow-up visits, CA-125 levels, pelvic ultrasounds and/or CT scans, depending on your case. Your healthcare provider will also perform pelvic examinations. It is very important that you let your healthcare provider know about any symptoms you are experiencing and that you keep all of your follow-up appointments.

Fear of recurrence, relationships and sexual health, financial impact of cancer treatment, employment issues, and coping strategies are common emotional and practical issues experienced by ovarian cancer survivors. Your healthcare team can identify resources for support and management of these challenges faced during and after cancer.

Resources for Patients

Foundation for Women’s Cancers

Offers comprehensive information by cancer type that can help guide you through your diagnosis and treatment. Also offers the ‘Sisterhood of Survivorship’ to connect with others facing similar challenges.

Cancer Care

Provides education, resources and support both online and by phone.

Chemocare

Provides information and resources about chemotherapy drugs

Sharp Hospital Cancer Support Groups and Services

Sharp offers a comprehensive range of support services to help you and your loved ones manage your cancer diagnosis and treatment.

Scripps Cancer Support Groups and Services

Scripps MD Anderson offers an array of cancer support programs, services and resources to help you every step of the way.

References

Targeted Therapy for Ovarian Cancer

Ovarian Cancer | Onco