What Is Endometrial Cancer?

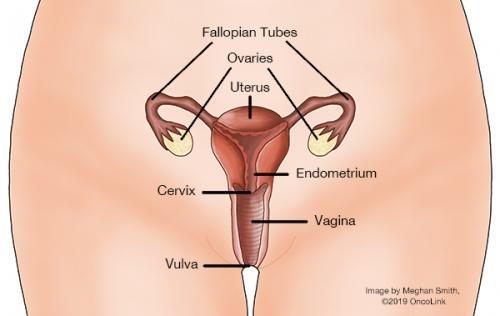

Endometrial cancer develops when cells in the endometrium (inner layer of tissue that lines the uterus) begin to grow out of control. Large collections of these out of control cells are called tumors. However, some tumors are not true cancers because they cannot spread or threaten someone’s life. These are called benign tumors. The tumors that can spread throughout the body or invade nearby tissues are considered true cancers and are generally called malignant tumors.

The distinction between benign and malignant tumors is very important in endometrial cancer. There are many benign (non-cancerous) processes that affect the uterus and may be confused for cancers. Fibroids (also called uterine myomas) are very common benign tumors of the muscle of the uterus (myometrium). Fibroids are not cancerous. They may cause increased vaginal bleeding, vaginal discharge, or pain. Your provider may suggest that you have your fibroids removed if they are becoming bothersome.

The most common type of endometrial cancer is called endometrioid adenocarcinoma. It comes from cells that form glands in the endometrium. This type compromises about 75% of all endometrial cancers. The second most common form is papillary serous adenocarcinoma (about 10% of all endometrial cancers), and another form is clear cell adenocarcinoma (about 4% of all endometrial carcinomas). Both papillary serous and clear cell adenocarcinomas tend to be more aggressive than endometrioid adenocarcinomas and are often detected at advanced stages. There are a few other rare types like mucinous adenocarcinoma and squamous cell adenocarcinoma that each account for less than 1% of endometrial cancers.

Another type of uterine cancer is sarcoma of the uterus. With uterine sarcoma, cancer is within the uterine muscle. Uterine sarcoma is very rare, and represents about 3% of all endometrial/uterine neoplasms. There are several subtypes of uterine sarcomas, including low grade endometrial stromal sarcoma (ESS), high grade ESS, undifferentiated uterine sarcoma (UUS) and uterine leiomyosarcoma (ULMS).

What causes endometrial cancer and am I at risk?

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecological malignancy in the United States. There is a 2.8% chance of a woman developing endometrial cancer during her lifetime. The majority of persons diagnosed with endometrial cancer are post-menopausal although it can occur in younger individuals as well. The average age of diagnosis is around 60 years of age.

One of the risk factors for developing endometrial cancer is age.

Additionally, those who are exposed to more estrogen (either naturally or from outside sources) are more likely to develop endometrial cancer. Several things can influence how much estrogen a person is exposed to such as: the number of lifetime menstrual cycles, starting menstruation at an early age, not having any children and no history of breastfeeding. Persons with these risk factors are all potentially more likely to develop endometrial cancer because their endometrium may be exposed to more estrogen over time.

Obesity is also a risk factor for endometrial cancer. Fat tissue converts other hormones into estrogens, so overweight people have higher levels of estrogen. Diabetes and high blood pressure, which also tends to occur in obese people, may be risk factors for endometrial cancer as well. Those who take hormone replacement therapy (HRT) after menopause are at a slightly increased risk for endometrial cancer.

A small percentage of persons who get endometrial cancer carry a genetic mutation called Lynch Syndrome. Lynch Syndrome is associated with a higher risk of colon and endometrial cancers, as well as other cancers including kidney, liver, kidney, brain and skin cancer. If a person has a particularly strong family history of endometrial or colon cancer (meaning multiple relatives affected, especially if they are under 50 years old when they get the disease), testing for Lynch Syndrome can be beneficial. Having a mutation doesn’t necessarily mean a person is going to get the disease, but it does greatly increase her chances compared to the general population.

It has been demonstrated that a diet high in animal fats and low in fruits and vegetables can increase your risk for endometrial cancer. Remember that all risk factors are based on probabilities, and even someone without any risk factors can still get endometrial cancer.

How can I prevent endometrial cancer?

Unfortunately, there aren’t very good screening methods for endometrial cancer. If you are a person without a family history/genetic syndrome, there are some things which are under your control and which can reduce the risk of endometrial cancer. Birth control (like OCPs – oral contraceptive pills, or Depo-Provera®) that stops ovulation/menstruation can reduce the risk of developing both endometrial and ovarian cancer. Multiple studies have demonstrated that OCPs reduce one’s risk for developing endometrial cancer; the longer a person takes them, the more they help in this regard. Combined hormone replacement therapy with both an estrogen and a progesterone component also appears to decrease the risk of endometrial cancer. However, both birth control and combined hormone replacement have several side effects. It is important to consult with your provider to see if they are right for your specific situation. Exercise also appears to reduce the risk of developing endometrial cancer. While a diet high in animal fats has been implicated in endometrial cancer, a diet rich in fruits and vegetables may have a small preventive effect.

What screening tests are used for endometrial cancer?

Currently, there aren’t any endometrial cancer screening recommendations for the general population (persons without hereditary cancer syndromes) because there aren’t any effective screening tests available.

What are the signs of endometrial cancer?

The most common presentation of endometrial cancer is post-menpausal vaginal bleeding. When a post-menopausal person has vaginal bleeding (present in 90% of individuals at the time of diagnosis with endometrial cancer), the first thing that needs to be looked into is the possibility of endometrial cancer. The most common signs of endometrial cancer include:

Vaginal bleeding (in a post-menopausal person).

Abnormal bleeding (including bleeding in between periods, or heavier/longer lasting than normal menstrual bleeding).

Pelvic or back pain.

Painful urination.

Blood in the stool or urine.

Unexpected weight loss.

All of these symptoms are non-specific and could represent a variety of different conditions.

Patients who are diagnosed with early endometrial cancers tend to respond to treatment better than patients with more advanced cancers, so it is beneficial to detect endometrial cancers as early as possible. Luckily, many endometrial cancers are found at early stages, because early endometrial cancers often cause vaginal bleeding (which is abnormal in postmenopausal person). All vaginal bleeding experienced by post-menopausal persons should be brought to a healthcare provider’s attention as soon as possible.

How is endometrial cancer diagnosed?

When a post-menopausal person has new vaginal bleeding, or any one has symptoms that suggest the possibility of endometrial cancer, their healthcare provider will want to get a sample of their endometrium. This is called an endometrial biopsy. A biopsy is the only way to know for sure if you have cancer.

The least invasive method to get a biopsy is to do it in your healthcare provider’s office. Occasionally, your healthcare provider may not be able to get enough endometrial tissue with an office biopsy. In this case, a dilation and curettage (D & C) may be recommended. D&Cs are done in the operating room under anesthesia. Your healthcare provider dilates the opening to your uterus and then removes endometrial tissue from the inside of the uterus, which can then be sent to a pathologist to be studied under a microscope.

Another technique that can help make the diagnosis of endometrial cancer is called the transvaginal ultrasound. By inserting an ultrasound probe into a woman’s vagina, the thickness of her endometrium can be visualized. This technique can help differentiate benign (non-cancerous causes of bleeding) from malignant causes of bleeding. If the endometrium appears too thick, then biopsies can be taken.

How is endometrial cancer staged?

Although surgery is required for staging, your healthcare team may also order some other tests to better characterize the tumor(s) and look for distant spread. Tests like CT scans or MRIs can examine the pelvis and localized lymph nodes. A CT scan of the chest may also be used to determine if there is spread of disease to the chest.

In order to guide treatment and offer some insight into prognosis, endometrial cancer is staged into four different groups. The staging system used for endometrial cancer is the FIGO system (International Federation of Gynecologists and Obstetricians).

American Joint Committee on Cancer (8.2018) and International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO), 2018.

|

FIGO Stages |

Description |

|

I |

Tumor confined to the corpus uteri; including endocervical glandular involvement |

|

IA |

Tumor limited to endometrium or invading less than one-half or more of the myometrium |

|

IB |

Tumor invades one-half or more of the myometrium |

|

II |

Tumor invades stromal connective tissue of the cervix but does not extend beyond the uterus |

|

III |

Tumor involving serosa, adnexa, vagina, or parametrium |

|

IIIA |

Tumor involves serosa and/or adnexa (direct extension or metastasis) |

|

IIIB |

Vaginal involvement (direct extension or metastasis) or parametrial involvement |

|

IIIC1 |

Regional lymph node metastasis to pelvic lymph nodes (positive pelvic nodes) |

|

IIIC2 |

Regional lymph node metastasis to para-aortic lymph nodes, with or without positive pelvic lymph nodes |

|

IVA |

Tumor invades bladder mucosa and/or bowel (bullous edema is not sufficient to classify as T4) |

|

IVB |

Distant metastasis (includes metastasis to inguinal lymph nodes, intra-peritoneal disease, or lung, liver, bone. It excludes metastasis to para-aortic lymph nodes, vagina, pelvic serosa, or adnexa) |

|

G |

Histologic Grade |

|

G1 |

Well-differentiated |

|

G2 |

Moderately differentiated |

|

G3 |

Poorly differentiated or undifferentiated |

How is endometrial cancer treated?

Surgery

Nearly all persons with endometrial cancer will require some type of surgery during the course of their treatment. There are two purposes of surgery; one, to stage the cancer, and two, to remove as much of the cancer as possible. In early stage cancers (stage I and II), surgeons can often remove all of the visible cancer. Generally, persons with endometrial cancer will have a hysterectomy (removal of the uterus) and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (removal of both ovaries and fallopian tubes). This is because there is always a risk of microscopic disease in both of the ovaries and the uterus. Your surgeon may also sample pelvic lymph nodes during the operation to look for possible cancer spread. Testing the nodes for cancer is very important as it helps direct additional treatment after surgery. This surgery is often done with robotic laparoscopy. This utilizes a small camera and smaller incisions to insert small instruments into the abdomen. The abdominal cavity is carefully inspected and biopsies from other areas of the abdomen to look for malignant cells may also be collected.

Those who have more advanced disease (stage III or IV) will often have debulking surgeries which require a larger abdominal incision and more recovery time. During this debulking surgery, the surgeon will attempt to remove as much disease as possible. In patients with very advanced cancers, surgery may be used for palliation. This means that patients are operated on with the goal of easing their pain or symptoms, rather than trying to cure their disease.

Short term side effects of surgery can include pain, infection, and damage to the bowel or bladder. Long term surgical side effects include intestinal obstruction or lymphedema.

Obstructions can be caused when scar tissue forms, trapping your intestines and preventing the passage of stool through the bowel. Lymphedema is caused by a build-up of fluid that our bodies normally filter as part of our immune systems. When surgery is performed and lymph nodes are removed, the lymph node drainage patterns can be altered, increasing the risk of lymphedema.

Radiation

Endometrial cancer is commonly treated with radiation therapy in addition to the surgery. Radiation is used to decrease the chances that the cancer will come back and has proven to be very effective in preventing local recurrence. Numerous trials have demonstrated that adjuvant radiation (radiation given after surgery has removed the cancer) significantly decreases local recurrence rates (cancer that returns in the same area). Radiation therapy uses high energy x-rays to kill cancer cells. Radiation is generally used in all but the most favorable cases (very early stages with low grades, and little invasion). Radiation can also be used in place of surgery in patients who are too ill to risk having anesthesia.

Radiation therapy for endometrial cancer either consists of x-rays delivered from the outside of the patient (external beam radiation/EBRT) or from a radioactive source placed inside the vagina (brachytherapy). External beam radiation therapy requires patients to come in 5 days a week for up to 6 weeks to a radiation therapy treatment center. The treatment takes just a few minutes, and is painless. Brachytherapy (also called intracavitary irradiation) allows your radiation oncologist to “boost” the radiation dose to the tumor bed. This provides an added impact while sparing your normal tissues. This is done by inserting a hollow tube (that contains a small radioactive source) into your vagina for a few minutes. This type of brachytherapy is called high dose rate (HDR) brachytherapy, and can be performed as an outpatient procedure. Based on the results of your surgery, pathology results, and imaging, your doctors may recommend brachytherapy alone, brachytherapy with chemotherapy, external beam radiation alone, or may recommend a combination of these.

For patients with more advanced disease, radiation is frequently given along with chemotherapy. Radiation can cause bowel irritation with diarrhea, and bladder irritation, which can cause frequent urination. Additionally, in the long term, the vagina can form scar tissue, which can make intercourse and future gynecological exams uncomfortable or even painful. Frequently, because of vaginal dryness, lubrication may need to be utilized during intercourse following radiation. After the acute vaginal inflammation resolves following radiation, a vaginal dilator should be used several times a week, indefinitely (or alternatively, regular intercourse), to reduce the severity of scar tissue formation and problems that can result from vaginal scarring. Aside from improving comfort levels during sexual intercourse, use of a vaginal dilator also helps to make regular pelvic exams more comfortable and allows the physician to view the areas more fully. Radiation can also increase the risk of bowel obstruction and lymphedema as a result of scar tissue formation.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the use of anti-cancer drugs that go throughout the entire body and is frequently used in endometrial cancers that are very advanced, or which have recurred. There are many different chemotherapy drugs, and they are often given in combinations. Different chemotherapy regimens are used for different subtypes of uterine cancers. Some of the chemotherapies used in endometrial cancer include: cisplatin, carboplatin, doxorubicin, topotecan, ifosfamide, docetaxel, pembrolizumab, and paclitaxel. There are advantages and disadvantages to each of the different regimens that your healthcare team will discuss with you. Based on your own health, your personal values and wishes, and side effects you may wish to avoid, you can work with your healthcare team to come up with the best regimen for your cancer and your lifestyle.

Follow-up Care and Survivorship

Once you have been treated for endometrial cancer, you will need to be closely followed for a recurrence. Generally, it is recommended that you follow up with your healthcare team every three to six months for the first two years, then every 6 to 12 months for the next three years if everything appears normal. It is very important that you let your healthcare team know about any symptoms you are experiencing and that you go to all of your follow-up appointments. The highest chance for a recurrence is in the first 2 years after the completion of treatment. Those with low risk disease, there tends to be a very small risk of recurrence (less than 5%). The majority of recurrences (70%) occur at the top of the vagina and cause symptoms such as vaginal bleeding, abdominal pain, or weight loss, and these should be reported to your healthcare provider immediately if they occur. Recurrences can occur in other more distant organs as well. Your healthcare team will tell you when he or she wants follow-up visits, CA-125 levels and/or CT scans depending on your case. Your healthcare provider will also perform pelvic examinations during each of your office visits.

Fear of recurrence, relationships and sexual health, financial impact of cancer treatment, employment issues and coping strategies are common emotional and practical issues experienced by endometrial cancer survivors. Your healthcare team can identify resources for support and management of these practical and emotional challenges faced during and after cancer.

Resources for Patients

Foundation for Women’s Cancers

Offers comprehensive information by cancer type that can help guide you through your diagnosis and treatment. Also offers the ‘Sisterhood of Survivorship’ to connect with others facing similar challenges.

Cancer Care

Provides education, resources and support both online and by phone.

Chemocare

Provides information and resources about chemotherapy drugs

Sharp Hospital Cancer Support Groups and Services

Sharp offers a comprehensive range of support services to help you and your loved ones manage your cancer diagnosis and treatment.

Scripps Cancer Support Groups and Services

Scripps MD Anderson offers an array of cancer support programs, services and resources to help you every step of the way.

References

All About Endometrial (Uterine) Cancer | On